Brainstorms I: Depression

An introduction to the science behind depression

Let’s start with an introduction. My name is Laura and I am a current MSc student in neuroscience and future PhD in psychiatry. In these last years, I have come to realize how little communication there is between scientists and the rest of society. Science is always advancing, creating new tools and obtaining new knowledge that can be of use to everyone, or that can pose new ethical questions on which society as a whole should have a say. But how is anyone going to take advantage of the new information or generate a debate with it, if it is not made available to them in an accessible and comprehensible way?

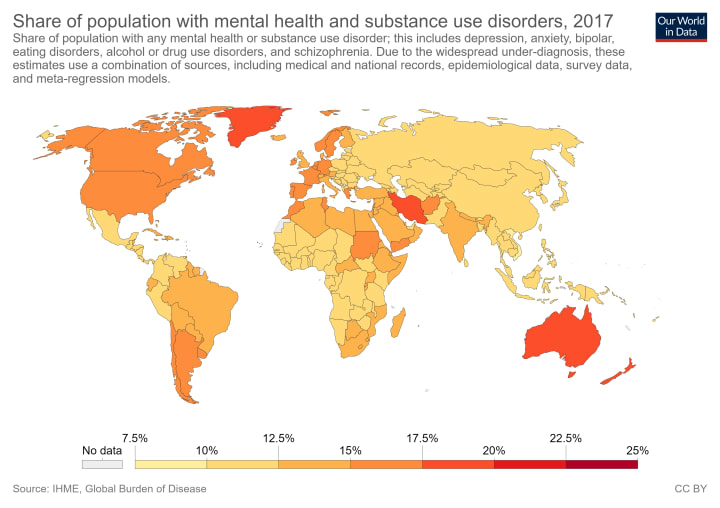

Therefore, I have decided to make my field of research accessible to everyone. With the rising numbers of mental health disorders and the stereotypes that I have encountered when talking about them, I thought it was necessary to deliver the information that science can give to the public about these diseases, to help society, and especially patients, understand what we know about them. Just as an example of how important these disorders are currently (with ever increasing numbers) here are some estimates on the numbers of people affected by different types of mental disorders and the disability rates caused by said illnesses. I think you will find that just with numbers it is already obvious that we need to do something about it.

Percentage of the population with a mental health disorder. The individual percentages might not seem like much, but think of the actual numbers behind the percentage! And remember that each percentage is PER COUNTRY, not globally. Image obtained from Our World in Data.

Percentage of the days lived with disability and lost years of life due to mental disorders. Again, remember these percentages are per country. Image obtained from Our World in Data.

Depression: an introduction

I decided to start with depression because it is one of the most commented mental disorders. But do people really know what depression is and how it affects people’s brains?

Before I start with the pure science behind depression, you can check the signs and symptoms of this disease here. Briefly, depression is characterized by a feeling of persistent sadness or anxiety, low energy, feelings of worthlessness or guilt, changes in sleeping and eating patterns and in the most extreme causes, thoughts of death or suicide, or self-harm and suicide attempts. If you are feeling any of these symptoms, please visit your doctor as soon as possible. If you don’t know where to go or how to deal with these feelings, tell at least one of your family members or friends so that they can lend you a hand seeking professional help. Depression is a serious illness and as such, you should be attended by a doctor and /or psychologist to guide you out of it. There are treatments and it can get better, but it is necessary that you get help. I cannot stress this enough.

Let’s move on now to the more hardcore facts on depression. Don’t worry, I’m not going to flood you with scientific terms and analyses. The whole point of this is that making science less scary so that we can all be awed by our brains. So read on.

Location of the PFC and the hippocampus in the brain. Image designed using bioRENDER.

Depression is the lead cause of disability worldwide. Yes, disability. This is not a choice of the patients, but a consequence of having the disease that modifies some of the structures in the brain, particularly the prefrontal cortex, or PFC, and the hippocampus. The PFC is involved in what are called “executive functions,” which really means making decisions and plans (including long-term ones), problem-solving, self-control. A whole lot of stuff, but the region we call PFC is quite a chunk of the brain, so it stands to reason that it would have a lot of functions. On the other hand, the hippocampus is involved in new memory formation (including spatial memory) and learning. Since there are physical changes in their brain, depression patients need time for treatment and recovery, they cannot just “get over it.” No one would ask someone with a broken leg to run a race; let's not ask depression patients to deal with their life as they normally would. This is not to say that all patients are equally unable to continue their lives. Each patient has a different degree to which their memory capacity, for example, is affected and, in turn, a different degree to which they can continue as they had before the onset of the disease. But do remember that the most extreme manifestation of depression is suicide, i.e. depression can be a cause for death. In fact, suicide is the second cause of death among adolescents. Let's leave patients their space and time to heal.

What does science tell us about depression?

People that suffer depression many times describe the experience as being in a cloud of grey. Nothing motivates them anymore, and everyday chores can prove impossible for them even though they seem physically capable and healthy. But that is the problem with mental disorders. These diseases can stay hidden in a person's head and no one would necessarily know. This poses a difficulty for the doctors and the researchers that try to understand what is going on in the brain of the patients. However, research is always shifting, adapting to the complications of whatever scientists are looking into, and therefore, solutions are coming up to study depression and other mental illnesses.

Like many other psychiatric disorders, depression has both biological and environmental factors that contribute to the appearance of the disease. To put it simply, a biological factor could be a gene (the instructions that code how we are made) and an environmental factor could be a traumatic experience. Both biology and life experiences can interact to induce depression in a patient. This, of course, makes it harder to study depression than if only biological factors were involved. Additionally to this, there is no single biological factor for depression. It is considered that the genetic component of depression (also known as heritability or how likely it is that the disease is transmitted from parents to their children) is 30-40%, but because of its complexity, the subtypes and the diversity of patients and symptoms, it has been complicated to pinpoint the specific genes that could be hidden in that 30-40%. However, researchers have been able to find a few genes involved in depression. This is what I will explain in the following paragraphs.

The first candidate for depression is a molecule called BDNF (Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor). This factor is involved in the generation and maintenance of healthy neurons and connections. Patients with depression have less BDNF levels. As others have already talked about this in an accessible way, I won’t go over it, but you can read a bit more on this here.

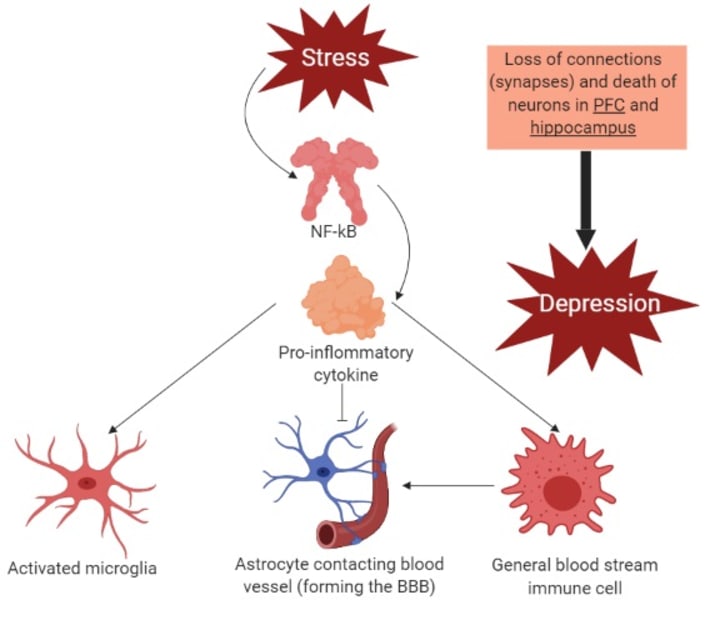

The second candidate is the immune system, and specifically the molecule NF-κB (nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells). This system is crucial to keep our body free from harmful germs, but it is important to keep it under control too, as it can attack our own body if something goes wrong, as is the case in autoimmune diseases.

The immune system plays a role when we think of depression caused or related to excessive stress. Stress is not a bad thing per se, as it can help us be more efficient, enhance our memory capabilities or escape immediate danger if it is short lived. However, if we are exposed to constant or chronic stress, the effects can be very harmful. Stress can activate the immune system through NF-κB, which will provoke the release of molecules called pro-inflammatory cytokines. Generally, the immune system of the body is separated from the immune system of the brain, because the cells of the brain (called neurons and glia) are recognized as foreign by the immune cells of our body. So, basically, if our general immune system infiltrates the brain, our brain cells will be under attack. Pro-inflammatory cytokines will lead to increased inflammation in our body and they can also travel into the brain and cause the activation of the specific immune cells present there (microglia) and of the astrocytes, which are both a type of glial cell. On the one hand, activation of the microglia generates an inflammatory reaction in the brain that can decrease the connections between neurons (synapses) and stop the generation of new neurons, which happens specifically in the hippocampus in the adult brain (remember that the hippocampus was one of the key regions involved in depression, together with the PFC, which we will see here shortly). On the other hand, astrocytes are very important glial cells that help to keep neurons healthy. They have many functions, but today we are only interested in the maintenance of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and the metabolic regulation of neurons. The BBB is the wall that keeps the general immune cells out of the brain. When astrocytes are activated by pro-inflammatory cytokines, however, they make the BBB less strict, potentially allowing immune cells to enter and wreak havoc in our brains. However, the break in the BBB seems to happen specifically in the PFC in patients with depression, so not all parts of the brain are affected. So now we have the two regions generally pointed to in depression involved in the detailed mechanisms that science has found involved in this disease.

But pro-inflammatory cytokines are not satisfied with this and they also alter the metabolism of astrocytes, which disbalances the energy supply to the neurons. The attack by immune cells and the loss of energy causes the neurons to pull away from their points of connection with other neurons, breaking the information flow. This by itself can already be the cause of a malfunctioning system that causes disease, but it can also induce the death of neurons, which will obviously make it all worse.

Schema representing the effects of NF-κB leading to depression. Image designed with bioRENDER.

So now we know a bit about how depression starts. But, unfortunately, this is not the whole story. There are more mechanisms that can initiate depression apart from the ones I wrote here. Then we also have to ask ourselves, how can it be so specific to certain parts of the brain? Why does depression affect women more commonly than men? How do antidepressants work and why do they sometimes not work? I will try to answer these and other questions in my future posts. Stay tuned!

References

General websites and blogs:

Scientific papers:

- Ménard, C., Hodes, G. E. & Russo, S. J. Pathogenesis of depression: Insights from human and rodent studies. Neuroscience 321, 138–162 (2016).

- Kraus, C., Kadriu, B., Lanzenberger, R., Zarate, C. A. & Kasper, S. Prognosis and improved outcomes in major depression: a review. Translational Psychiatry 9, (2019).

About the Creator

Laura Sotillos Elliott

Future doctor. Interested in science communication in all its forms: writing, podcasting, organizing scientific events...

Follow me on twitter at @addict_science

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.