The Girl Who Remains

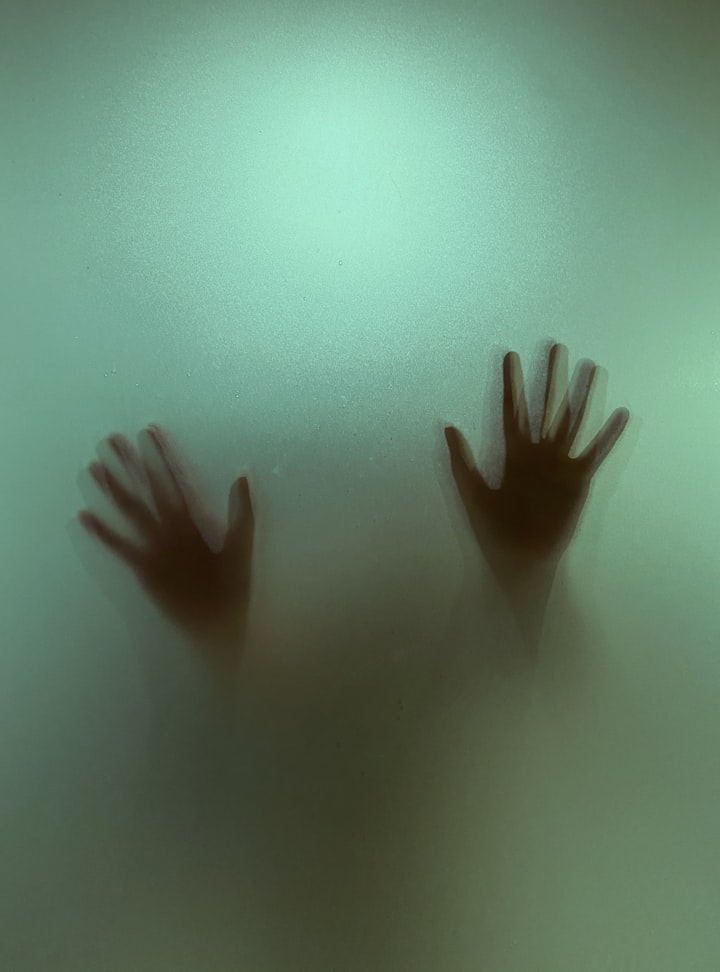

An Excerpt from a Suicide Survivor Saga

Each day, a little of our yesterday fades away. A memory blurs into a forgotten moment forever lost in the past. A lock of hair clipped away, a favorite over-worn pair of sneakers we finally discard, a hand-written letter with missing words in faded ink. We keep sentimental relics but do not always realize their significance until the devastating period of retrospect requires them to remind of us a happy once-was that we can no longer conjure in the present. Every new cycle, we transform ourselves into a new us, on each new today — though time is relative. We brace ourselves for what lies ahead in each new tomorrow. Only tomorrow seems as distant as yesterday when our sadness causes time to screech to a halt.

There was no proverbial wisdom to prepare me for the loss I suffered two springs ago. To say a part of my heart died is metaphorical; it continued beating on that day, as it had the day before, and still does today. It would be more biologically accurate to say my hippocampus was imprinted with a haunting memory. That a neural synapse in my limbic system was permanently altered. The nineteenth of March was the day I watched a man I loved very much take his last conscious breath. He muttered his last words weakly, as his right hand clasped mine firmly at first, then frantically, and then — his hand went limp as I squeezed it harder and sobbed as I placed it against my tear-drenched cheek.

No one ever foresees themselves suffering a moment of tragedy like this. Unlike a mother getting a visit from a military messenger informing her that her son is not returning from his station of combat duty. A soldier whose life ended prematurely while fulfilling a service obligation that led to his demise in a foreign land, leaving behind grief-stricken relatives who never had the chance for a last goodbye. No, my goodbye tore my heart to shreds. I watched my love tell me that he wanted to go, he told the paramedics the same. And yet, I fought to keep him. I told myself his personal anguish had clouded is judgment, that he needed me to get him through the down slope, that maybe if I got him to tomorrow, it would be a brighter day. But tomorrow never came for him. It did for me. And the next day, and the next, and I didn’t know how to resume functioning when I had been consumed in trying to “save” him from himself for two heartwrenching years. I felt empty, like a failure. I had failed him. I deserved to suffer, while he was finally at peace.

I had met J several Octobers before. He was with his two sons and fiancée at my son’s seventh birthday party. He was a gentle blue-eyed electrician who offered to repair a broken outlet on the front porch of my house. A proud father who gleamed as his six year old swung a broken broomstick at a piñata we’d acquired for the festivities. I would have never guessed the man I met on that day was hiding such a troubled mind behind that friendly smile he presented as a respectful houseguest. As a new father to a three-month old infant, Xavi, with a beautiful quiet girl at his side in a pretty white dress with blue flowers and a more matter-of-fact demeanor.

He seemed to have the life that many men have only dreamed of. A happy family, a companion he adored, an established career, and a happy twinkle in his eyes on that day that belied the misery that lurked beneath the surface. It came as a surprise to me when several months later he contacted me, trying to reach out to my sister who had been a friend to him. She had been the one who invited him to N’s party that fall. Somehow, I inherited his friendship. He seemed heart broken, lost as he and his love had parted ways, and looking for someone to listen as he processed once again living alone, empty and aimless, disappointed to lose the dream life he had less than a year before.

What I have learned is what everyone tells us, and no one ever comprehends from the tragedy of another. It takes experience in our own form of loss to realize trauma as we experience. We would never wish our pain on anyone else, and yet, we often feel trapped and alone in our own personal hell, desperate to recover our former self. Yet sadly aware that our trials mold us a bit more harshly than times of joy ever do, for happiness is fleeting and rarely soaks in as deeply as bitter despair. Sometimes the pain becomes a dark familiar companion that carries us through what seems a minimal survival mode at best. But not everyone survives. The only ingredient that helps us survive heartache is time, in a life sentence that measures differently for each of us.

The girl who remains in this story in me. I am a suicide survivor. A woman with a death on her conscience that changed who I am forever, for better or worse. The guilt in the immediate aftermath consumed me. It made me an angry, spiteful person who pushed away anyone who instructed me to seek “help.” Help was a four letter word to a registered nurse who had memorized the scripts that medical professionals deliver to each patient along with their favorite psychotropic medication of choice. I just was too smart, too cynical, too self-aware, too engulfed in the drowning waves of grief that overtook me as I thought I could control my own healing process. I was wrong.

Survivor guilt never makes sense to an outside observer. I was told by so many others that, no — it was not my fault that on a particularly bad day, J got the courage to finally take the action required to end his own life. Deep down, every person who has lost a loved one to this stigmatized manner of death knows that the responsibility ultimately lies on the person who made the choice. Except that person is gone. That person is not suffering anymore, but the left behind are. I was.

I never glorified J or put him on a posthumous pedestal. He wouldn’t have wanted that. But what he wanted, didn’t matter anymore, not to him. Only to the ones left behind who each carried their own version of guilt and emotional damage for “failing to save” this troubled soul who held a special place in each of our hearts. It wasn’t just a part of my heart that died on that day. Two boys lost a father, two young mothers lost a co-parent, two young men lost an older brother and role model, two parents lost a child... Kristy, his mother, has essentially adopted me as a daughter and co-captain in the plotting of operation “Keep J Alive” for the two years I tried to adapt to his cycles. The emotional rollercoaster eventually caused my own collapse. I inherited a role as a codependent enabler in a drug addiction, not just for him but for those he had learned to carry while tormented in his own personal struggle. To say I didn’t like it is an understatement. To say I remained innocent is a lie. I received a crash course in suicide survival, though the ones who knew him his whole life were no more prepared for his death than I was. This loss shook me to the core. All of us and none of us could have predicted or prevented the emotions he experienced on the day that J took his own life. We have uttered a thousand what-ifs in self-doubt, but who is to say that an alternate action pondered in hindsight wouldn’t have triggered an equally crippling state of mind for him on that day?

There is no knowing, no understanding. Half the battle is accepting the answers we will never have. There is no closure in surviving. There is just coping with what has been left behind, and acknowledging what we choose to carry with us in our lives that follow once their physical presence is no longer possible. The cross is so heavy at first that we stagnate. We dwell on the loss until it nearly kills us, too, or so we think. But if we distract ourselves for long enough, it doesn’t. The trick is to allow ourselves, to force ourselves if necessary, to seek out the distraction. We feel obligated to mourn for an indefinite amount of time. We never really know how long we need to “move on,” and aren’t convinced that moving on is possible. Until one day we wake up and realize we had a pleasant dream in the place of the usual nightmare. We have to talk ourselves out of the guilt we feel for having the pleasant dream. It is a vicious cycle.

But it is a work in progress. My story is a work in progress. But I am here. I am a suicide survivor...

About the Creator

Amanda Karenina

I'm nobody.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.